From my previous blog: Second century Church Father St. Irenaeus of Lyon famously wrote, “The Glory of God is a human being fully alive.” God has called us to be participants in His divine nature, bringing His reconciling life to the world through worship. So, why do we often find ourselves “running on empty,” lacking in inspiration and motivation? How do we get into these dark and difficult spaces, and how do we find our way back to intimacy with God? And, how do we continue to lead our congregations in worship with authenticity and Godly passion through challenging circumstances?

To some extent probably all of us have been spiritually empty, dry, dull, devoid of joy, devoid of life, frustrated, unhappy, discontent, completely out-of-sorts with God, with our families, with our brothers and sisters, seemingly out-of-sorts with the entire world, and, more to it, even out of sorts with ourselves.

When we find ourselves in this spiritual state, awakening like the prodigal son in the pig pen of existence, lost, hungry, discouraged, lonely, how do we get home?

In Part One of this blog, I wrote about the first cause of spiritual emptiness, sins of commission and omission. The second great cause of spiritual emptiness, the focus of this blog, is a result of what happens to us, what comes upon us through little or no fault of our own. This category falls into the realm of theodicy. Theodicy is generally the study of the problem of suffering and evil in a world created by a personal, providential God of infinite goodness. It’s an attempt to justify God in the face of suffering and evil. While this tends to lean toward an academic study focused on proving the existence of God, theodicy becomes very practical indeed when stuff happens to you: long-term illness, death of a loved one, loss of employment, conflicts in friendships or marriage, oppression, prejudice, tragedies, disasters, even terrorism, etc., whether these circumstances be personal, or in the family, or in the community or society or culture. Theodicy is terribly difficult and potentially deeply discouraging.

This is perhaps the most difficult and challenging of all theological issues. All supposed answers seem facile and fall short of explaining how God, who is ultimate goodness, truth and beauty, can allow in his creation what seems to be evil, even unspeakable evil. Why doesn’t God intervene? Why are we left to suffer? How do we find meaning in that suffering?

Many have attempted to find meaning in difficulties, Christians and non-Christians alike. There are it seems two “easy options,” as Bp. Robert Barron calls them. First, there are some who ascribe suffering to divine retribution, or God expressing his anger against recalcitrant mankind.

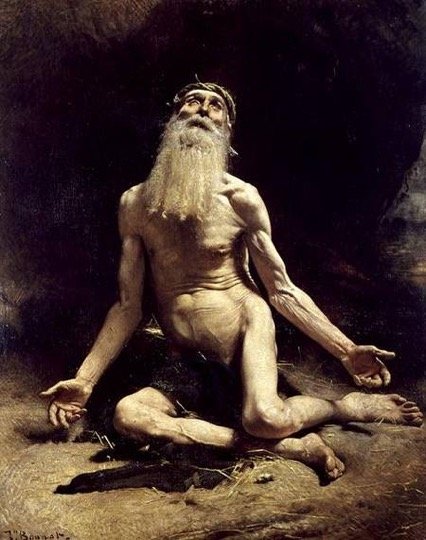

The problem with that perspective is found in the Book of Job. Job is, of course, the biblical archetype of the suffering human being who has undergone the worst kind of suffering and loss. Job’s “friends” use that same argument: “Surely, Job, you have done something, because God would only attack you in this way if you had done something to deserve it.” But Job rightly says “no.” Then the Book of Job presents a much more nuanced answer to the problem, refusing this “easy option.” The second option is the position raised by atheists and agnostics—The existence of suffering proves there must not be a God at all, or the possibility is at least not likely, or else why would these things happen? How can God be reconciled with such evil and suffering? So, either you did something wrong to make God mad, or there really is no God. Both of these options are too easy and not helpful to the sufferer. And, frankly, they are just mistaken.

St. Augustine argued that evil is sometimes a necessity to bring about a greater good, as in just war or the death of a martyr. (Church Father Tertullian wrote, “The blood of the martyrs is the seed of the church.”). St. Irenaeus seemed to argue that suffering is a necessary evil for the development of free moral agency in humans who are striving for godliness. Origen saw suffering as a kind of opportunity for schooling, or healing of the soul.

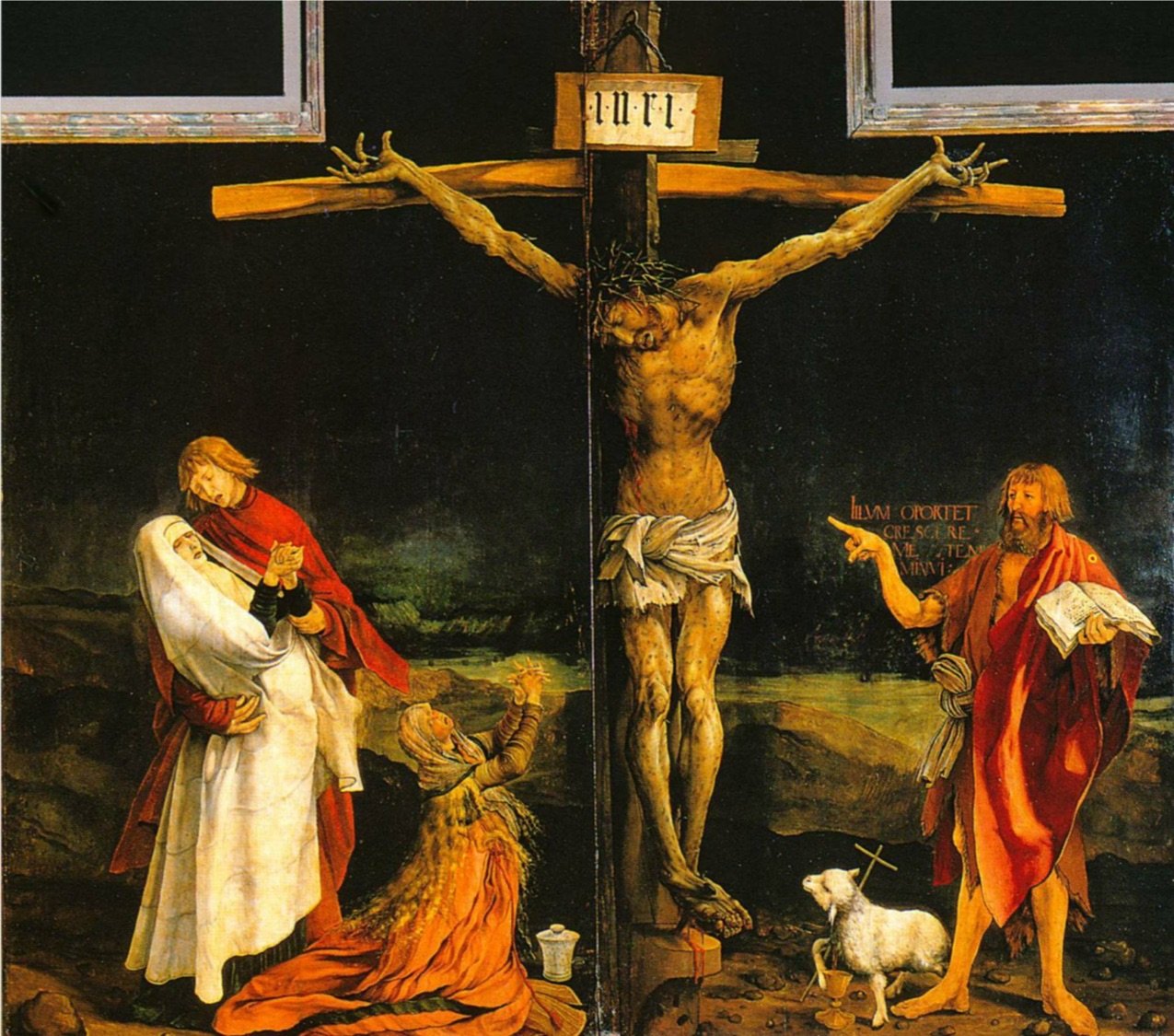

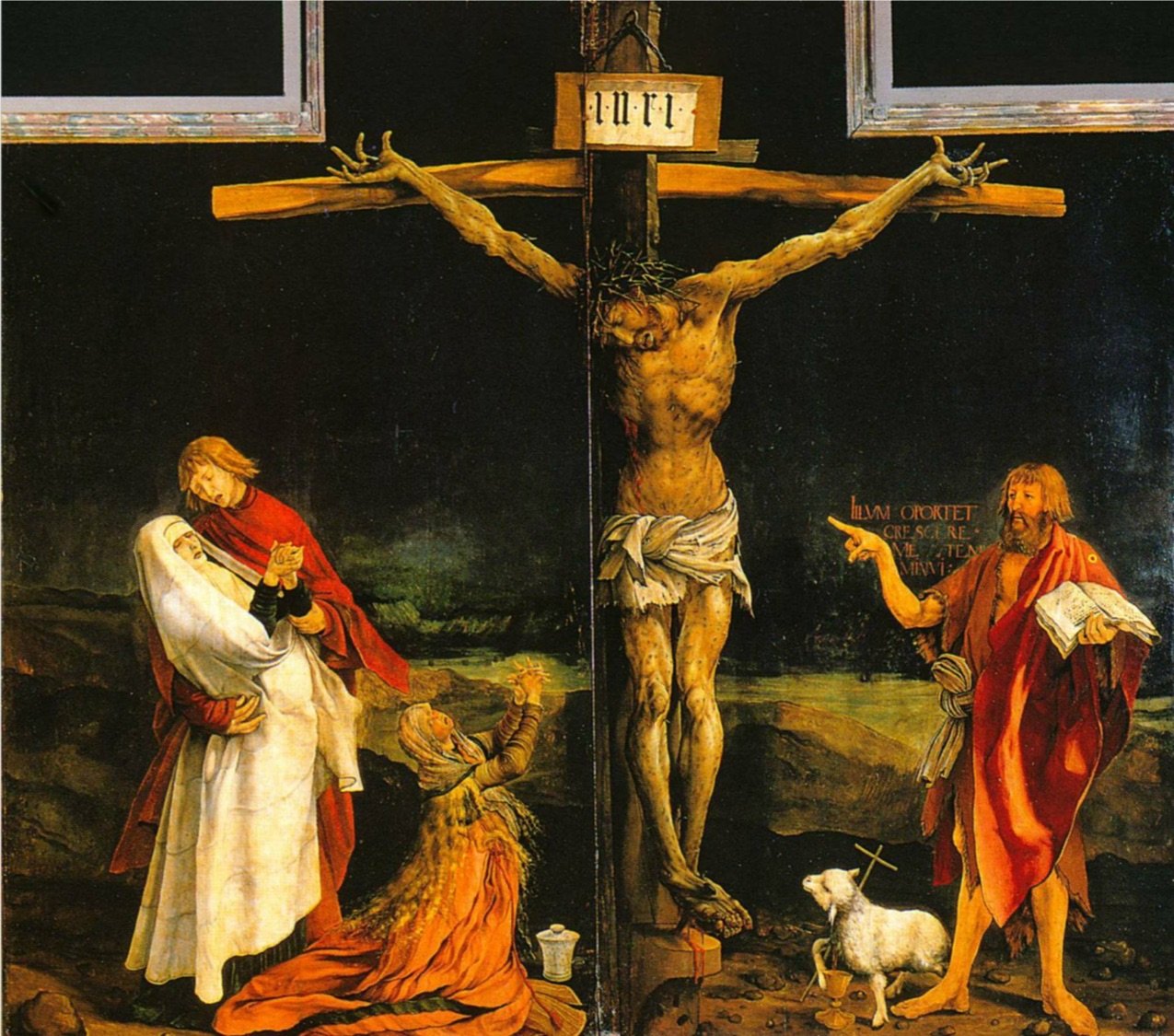

Some see the crucifixion of Jesus as God’s identification with and, in reality, the summation of our suffering, justifying God’s use of suffering to mold us into the fullness of his image. But, all of these “explanations” fall short for those who are suffering.

While this blog won’t resolve the issue of theodicy, let me at least provide some thoughts that perhaps gesture towards a way to interpret suffering.

First, God can never be construed as the cause of evil. Why? Because God is love, through and through. That’s all he is. God cannot will something evil, something that does not contribute to human flourishing. More to it, God is described as being itself. Therefore, God cannot be the cause of the non-being of evil. Evil in the metaphysical sense doesn’t exist. Rather, it is the privation or absence of the good, not a complementary equal and opposite “yin” to God’s “yang,” like the dark side of the force! Rather, evil is a lack of good that ought to be there. So God cannot cause evil directly. Instead, God seems to permit evil to bring about a greater good. The free will that God gives all of us allows for the abuse of free will. That is sin, and sin has consequences. So, God doesn’t cause evil.

Second, the good we do to others to relieve their suffering can be construed as an expression of God’s loving care, as the vehicle through which God operates. Why would God not bypass us and act directly to relieve suffering? Thomas Aquinas answered that the supreme cause (God) is pleased to involve us in his causality, giving us, as it were, the joy and privilege of sharing his work. In other words, God calls us to share in his loving care of others.

Third, believers in the God of the Bible should not expect that they will be free of pain. Rather just the contrary is true. It is actually a bit of a puzzle that so many readers of the Bible seem to think that the love of God is incompatible with suffering, when all of the major figure in the Scriptures—Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, Joseph, Moses, Joshua, Samuel, David, Isaiah, Jeremiah, Ezekiel, Daniel, Peter, James, and John—all of them, go through periods of enormous suffering.

And this puzzlement only deepens when we recall that Jesus, the central person in the Bible, is typically displayed to us nailed to a cross and in the throes of death. Suffering may be interpreted therefore as a participation in the salvific agony of Christ. Paul tells us in numerous places that we should participate with Christ in those sufferings.

Fourth, suffering tends to give rise to love in others. As we suffer, others become awakened to the compassion in them. In a word, the sufferer’s pain can have a saving effect on those around him or her; to use the language of the Bible, the sufferer suffers on their behalf. In Col 1:24: Paul writes, “Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I am filling up what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church. Our triumphs and joys are never utterly our own; they are for the sake of others. And the same is true of our tragedies.

When we look at the good and evil of this universe, we only see a microscopic speck of God’s intentions in history. Making determinations on that very limited viewpoint would be like reading a sentence from a classic novel and determining from that one sentence the overall scope and meaning of the entire book. Foolish at best, but deadly and life-draining at worst.

Do these interpretations “solve” the problem of innocent suffering? Obviously not. But do they shed light in a creative way on key aspects of it? I think they may.

Back to Job. In the Book of Job we find that this man Job, again the archetype of the suffering human, has, in one fell swoop, lost all that counts toward human flourishing: his health, his wealth, his family, his livelihood, even his friends. It is all taken away. And, he knows he is a good and an innocent man. There he sits in spiritual, physical and emotional agony. How could God have possibly allowed this to happen? Job then endures his friends’ pathetic, relentless and insensitive explanations. At the climax of the story, Job dismisses his friends and calls God into account. Why am I suffering in this way? What ensues is Chapter 38 and following, God’s longest speech anywhere in the Bible. God says, “Where were you when I made the heavens and the earth? Where were you when I laid the foundations of the world? Where were you when I told the sea where to stop? Where were you when I stored up the wind and the hail?” He takes Job on the tour of the cosmos, revealing to him all of the mysteries and glories of the created order. God doesn’t specifically answer the problems of Job, but situates his suffering in the ever-widening framework of meaning. God is the Lord of all of space and time, and has providential care for everything. Whatever we are experiencing is in the context of an infinitely wider and more complex created order and purpose.

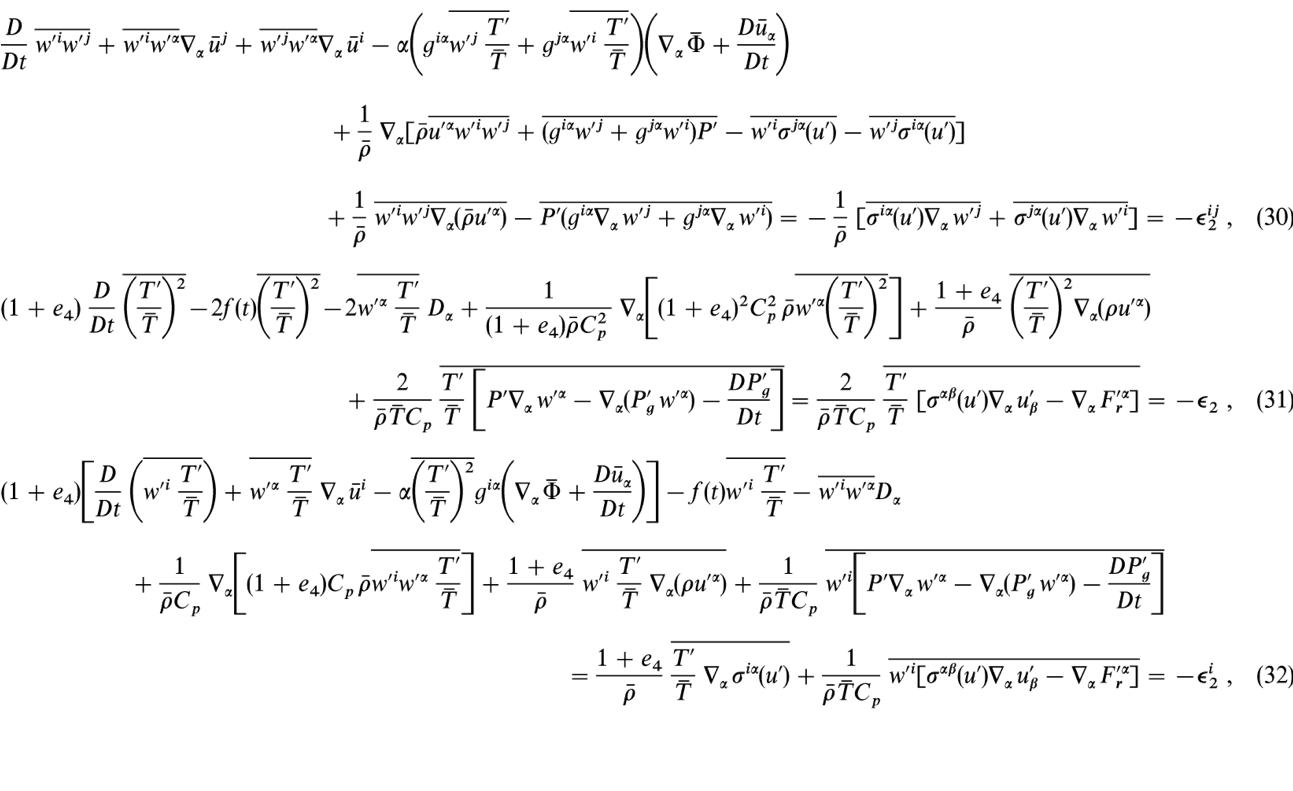

It would be like someone who knows no mathematics stumbling upon a complex astrophysics formula and determining its meaning. So, if you know no math, it would be impossible to determine the meaning of this formula, let alone arrogant to try. The awareness of the various contexts for our experiences is needed before we announce meaning or the lack thereof.

Our suffering can be seen as ingredient in a much larger story, as a route of access to a deeper and richer life, both here and in the world to come.

The Christian narrative is this: suffering and death is not the end nor the victor. Beyond suffering and death lies resurrection and true life, divine life.

James 1:2-4 reads, “Count it all joy, my brothers and sisters, when you meet trials of various kinds, for you know that the testing of your faith produces steadfastness. And let steadfastness have its full effect, that you may be perfect and complete, lacking in nothing.”

Let’s look at Matt 16 for a possible solution to spiritual emptiness:

(vv13-20) Now when Jesus came into the district of Caesarea Philippi, he asked his disciples,

“Who do people say that the Son of Man is?” And they said, “Some say John the Baptist, others say Elijah, and others Jeremiah or one of the prophets.” He said to them, “But who do you say that I am?” Simon Peter replied, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God.” And Jesus answered him, “Blessed are you, Simon Bar-Jonah! For flesh and blood has not revealed this to you, but my Father who is in heaven. And I tell you, you are Peter, and on this rock[a] I will build my church, and the gates of hell shall not prevail against it. I will give you the keys of the kingdom of heaven, and whatever you bind on earth shall be bound in heaven, and whatever you loose on earth shall be loosed in heaven.” Then he strictly charged the disciples to tell no one that he was the Christ.

Pretty heady stuff, isn’t it? Especially for Peter! The victorious Church is coming into existence, and the very gates of hell will not stand against it! But, for Peter especially, the story takes a quick turn:

(vv. 21-27) From that time Jesus began to show his disciples that he must go to Jerusalem and suffer many things from the elders and chief priests and scribes, and be killed, and on the third day be raised. And Peter took him aside and began to rebuke him, saying, “Far be it from you, Lord! This shall never happen to you.” But he turned and said to Peter, “Get behind me, Satan! You are a hindrance to me. For you are not setting your mind on the things of God, but on the things of man.” Then Jesus told his disciples, “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it. For what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul? Or what shall a man give in return for his soul? For the Son of Man is going to come with his angels in the glory of his Father, and then he will repay each person according to what he has done…”

In this passage, Jesus presents the only valid solution to suffering and evil and spiritual emptiness, and thereby the only valid pathway to real joy. It’s a great paradox, but Jesus’ solution to the problem of suffering and evil (and emptiness, really) is to sacrifice oneself in love. In giving away the self in love, we find our true meaning and our true purpose. The solution to spiritual emptiness, to suffering and evil, and the key to the entire spiritual life is to give yourself away in love for the other, becoming a source of life for the other. That is the Christian solution. Difficult? Yes! In fact, it’s a lifelong journey that is only possible in the power of Christ and His Spirit!

Do you know that God always has a mission for us, even in our lowest, emptiest times? In fact, it is an issue of spiritual metaphysics. According to Bp. Robert Barron, the divine life of God increases ONLY in the measure that you give it away. Try to hold on to it, to grasp after it, and it will decrease. Only by giving away the divine life of God can it increase in us. “Whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.” So, spiritual metaphysics indicates that to get out of a place of dryness or void or dullness, give, serve, find practical ways to love the other as other, expecting nothing in return.

In a very real sense, this is the entirety of the Christian life, being poured out in love, willing the good of the other as other. St. Augustine gave us the perspective that you are what you worship. You become what you adore. It’s not about our passion, our love of God, our desire to serve. I will never be passionate enough, love God enough, or serve with enough fervor. But I know a man who identified with my humanity, who is just like me in every way. He has done for me what I cannot do for myself. He is the chief worshiper in the Kingdom, making intercession for us right now at the right hand of the Father. He has taken my failures and sufferings forever to the cross, and has called me to follow him and take up his cross of self-giving love. His name is Jesus, and only through him can I love God as I should. Only through him can I love others as I should. And only through him can I find true joy, peace and reconciliation with God and man.

This is a poem scrawled on a wall in Germany by a Holocaust victim:

“I believe in the sun, even when it is not shining.

“I believe in love, even though I don’t feel it.

“I believe in God, even when he is silent.”

Why? Because He who created the universe, including us, from nothing, is truly and really and lovingly present with his creation, particularly with us, at all times.

In the name of the Father, and of the Son, and of the Holy Spirit.

Your pastoral commentary is so practical here, Jim. It is so easy to only see futility in suffering. Seeing not only utility in it but also sacred purpose is so redemptive.

Also, having a keener, more dynamic, perception of the spiritual warfare in which we are living also gives me helpful context – that the enemy of our souls is indeed making war on us because of his hatred of the one in whose image we have been lovingly made. At least that makes it less personal.

In the closing words of the Prayer the Master taught: “Deliver us from evil (or the evil one)” or “Save us from the time of trial.”

That is an important addition to what I have written here. Thanks, Darrell!